|

|

The UltraWide Survey - Mapping the Kuiper Belt

|

How do planets form? It's a question that's attracting a lot of attention

right now. Giant planets, probably made mostly of gas, have been found

orbiting distant stars. These extrasolar planets are fairly similar to

our own Jupiter, Saturn and Neptune. So to understand extrasolar

planets,

we'd like to first understand how our planets formed.

|

|

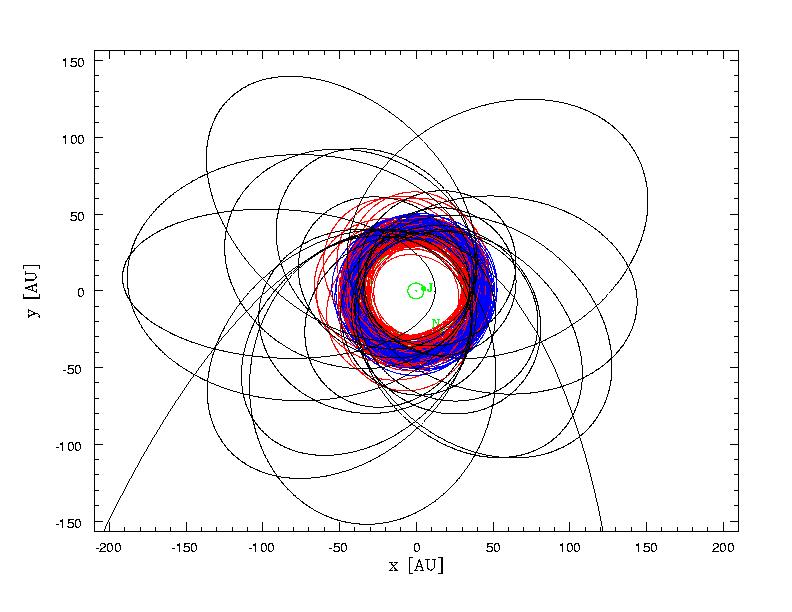

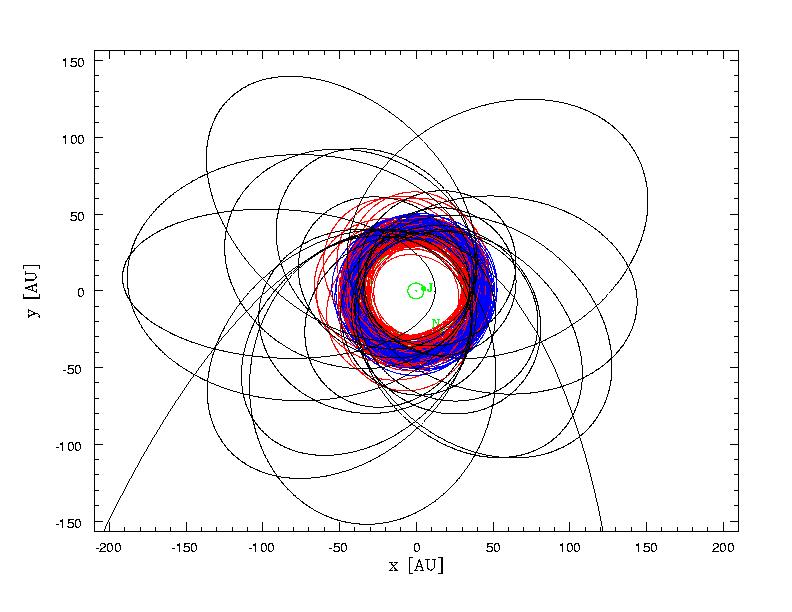

The answer may lie in the Kuiper Belt. The Kuiper Belt is a band of

chunks of rock and ice that circle our Sun out beyond the orbit of

Neptune. These Kuiper Belt objects (KBOs) are the leftovers of the disk

from which our Solar System was created. Because they formed so long ago,

and because they've been relatively undisturbed since, KBOs provide a

glimpse into the past. By studying KBOs, we can learn how our giant

planets were formed.

|

|

Studying KBOs is tricky to do. Because they shine only by reflected

light, KBOs are faint and hard to see. And because they're so far away,

the only way to be sure that an object is a KBO is to follow it for a few

nights to make sure it moves against the backdrop of stars in the proper

way. In spite of these difficulties, more than 400 KBOs have already been

found.

|

|

|

The CFHTLS UltraWide Survey wants to do better. It will find more

than 2000

KBOs, and so create the first comprehensive map of the Kuiper Belt. With

this many KBOs to study, we'll be able to answer some basic questions

about the Kuiper Belt: How far does it extend? How are the KBOs

distributed within it? And what is the largest KBO? Some astronomers

think the "planet" Pluto is just another member of the Kuiper Belt - maybe

we'll find a KBO even bigger than Pluto!

|

|

Mapping the Kuiper Belt will help us to better understand it, and so to

better understand how our Solar System formed. Armed with this knowledge,

we'll be able to study extrasolar planets with more insight and

comprehension.

|

This site was last updated on September 28th, 2002.

Comments, suggestions or questions? mlmilne@uvic.ca

|